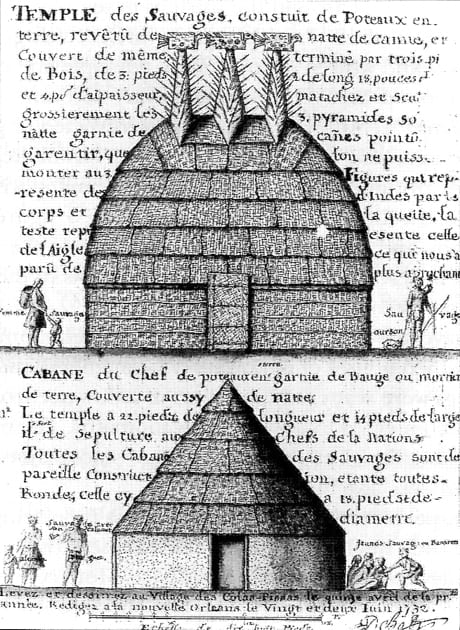

If you head up to Natchez, hop on the trace, and drive for about 11 miles, you will see a sign for place called Emerald Mound. Take a left on the appropriately named Emerald Mound Road, drive for about another mile, and on your right you will find one of North America's largest earthen structures. This obscure site was once the ceremonial center of an American Indian polity, probably the ancestors of the Natchez tribe. At one time several structures stood on top of the mound, the largest of which were likely the chief's residence and a temple. Archaeologists believe that Emerald Mound is eight hundred years old, and although only the earth remains today, it is the same age as some of the pueblos in the Southwest and the oldest Gothic cathedrals in Europe.

Emerald Mound is just one of the many such sites that can be found in the eastern United States. The construction of colossal earthworks began thousands of years ago in the Mississippi Valley and some of the oldest can be found here in Louisiana, including Poverty Point and the LSU Mounds. Emerald Mound belongs to a later era, known as the Mississippian Period, corresponding to what we call Medieval or the Middle Ages in Europe. During this time period, large mounds were constructed throughout the South and Midwest, on top of which stood temples and the houses of chiefs. Farming bloomed and was centered around the cultivation of the three sisters – maize, beans, and squash. Despite the growth of agriculture, the primeval forests of the southeast thrived, with millions of acres of hardwood trees giving shelter to now-extinct birds such as passenger pigeons and Carolina parakeets.

Charles Hudson, a historian who taught at the University of Georgia, dubbed this world "the Ancient South" to distinguish it from later Colonial Period. When the Spanish Conquistadors arrived on North American shores, they found these mound-building societies thriving. The chroniclers of the entrada, the Hernando de Soto expedition, gave us some of the most detailed reports of these cultures and recorded the names of the chiefs they contended with, including Tuscaloosa of Mabila (Mobile) and Quigualtam of a Mississippi chiefdom. However, the arrival of Europeans and Old World diseases, such as smallpox and typhoid, proved apocalyptic to Mississippian societies. Successive epidemics reduced the population to a small fraction of what it once was. Survivors regrouped, forming new confederations such as the Choctaw and the Creeks. The landscape itself changed as colonial culture pushed westward and the ancient forests were cleared. New tools like steel axes and saws made it easier to fell trees, which provided the timber for new settlements and made room for cotton plantations. Ultimately, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, and federal troops forced the greater part of the Southeastern natives, the descendants of the mound-builders, to move west into Oklahoma.

While you travel through the southern states, keep you eyes open for the remains of the Ancient South. At the library, you can learn more about the mound-builders and the Mississippian tribes.

The Ancient Mounds of Poverty Point

Arrowheads and Spear Points in the Prehistoric Southeast

Indians and Artifacts in the Southeast

Lost Cities of the Ancient Southeast

Mound Sites of the Ancient South

Early Art of the Southeastern Indians

Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms

Add a comment to: The Ancient South