In the first of a two-part series, we will take a look at the 1918 influenza pandemic and its effect on St Tammany Parish.

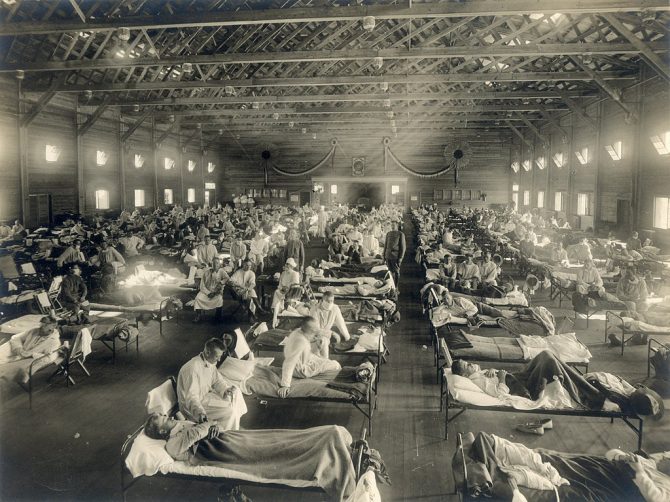

The 1918 influenza pandemic was devastating to the globe, causing mass casualties in nations that had already lost tens or hundreds of thousands to World War I. By the end of the pandemic, influenza had killed an estimated 50 million people - whereas the war killed an estimated 40 million. The culprit was an H1N1 virus which mutated and made the jump from birds to humans. There's no consensus on its origins, but at least one historian, John Barry, thinks that the virus originated in Kansas. Once it mutated, with the increase of international travel and wartime troop movements, it spread quickly. The influenza infected young adults disproportionately, and had a high mortality rate of 2.5%. It hit the United States in three waves: the first, in spring of 1918, went largely unnoticed, occurring in military camps during wartime. The second wave of infections arose in the fall of 1918; the third wave, in the winter of 1918 and spring of 1919. By its end, a quarter of Americans had been infected.

It was called the Spanish flu - a misnomer, due to Spain reporting heavily on the outbreak when the press of other countries was under wartime censorship. The symptoms were in line with a typical flu: fever, nausea, aches, and diarrhea. In more severe cases, patients developed pneumonia, and suffered severe earaches and headaches. The most unfortunate took on a blue shade - cyanosis - and those cases were considered terminal.

The first known case of influenza in Covington was attributed to Kenneth Moise, age 18, who took ill with it in September 1918. Moise had been stationed at Fort Sheridan, Illinois for two months for training. He had returned to Covington the week of the 21st, and had planned to spend a few days at home before returning to his studies at St. Stanislaus College in Bay St. Louis. Moise thought he had picked up the flu from a fellow train passenger; it is also highly likely that he picked it up at Fort Sheridan, where, by September 24, there were 120 cases of influenza.

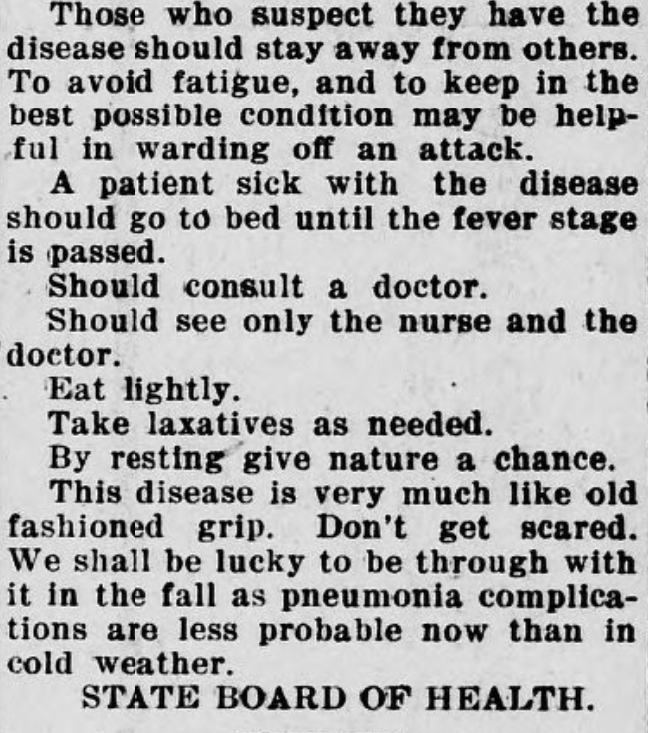

The case was reported by the family doctor, J. F. Bouquoi, to the Covington Board of Health. Moise's first test for the virus came back negative, but Bouquoi, in his certainty, urged a second test, and this one came back positive. The Council of Defense of Covington immediately ordered a quarantine of the Moise household, in which the disease had already spread to five other family members -- all apparently suffering mild symptoms. The Council then held a public meeting in which Dr. Oscar Dowling, director of the State Board of Health, advised residents to cover their sneezes and coughs, and to refrain from spitting on the sidewalks.

By early October, schools, theaters, churches, bars, and all public places in the parish were closed, with crowds not permitted to gather. In Slidell, five of their six telephone operators took ill, making communication difficult. Children, let out from school, were told to remain at home as much as possible. And the post office, usually a busy hub for the community, had officers stationed at the doors to allow only a small number of people in at a time. At this point, Slidell had 300 cases, and Covington had 22.

By early October, schools, theaters, churches, bars, and all public places in the parish were closed, with crowds not permitted to gather. In Slidell, five of their six telephone operators took ill, making communication difficult. Children, let out from school, were told to remain at home as much as possible. And the post office, usually a busy hub for the community, had officers stationed at the doors to allow only a small number of people in at a time. At this point, Slidell had 300 cases, and Covington had 22.

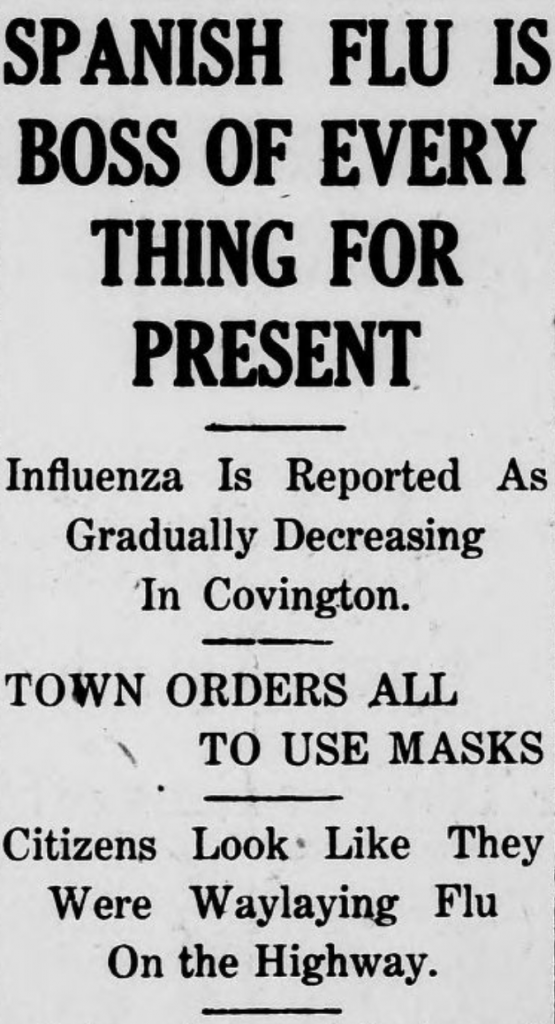

Every day brought an increase in cases. An October 19 headline summed up the situation: "Spanish Flu is Boss of Every Thing for Present". The parish by this time had 454 new cases, the highest peak thus far. Covington, Madisonville, and Abita Springs residents were told to wear masks - often with locally-made Mackie's pine oil applied as a germicide. In Covington, a fine of thirty dollars (the equivalent of $512 by current standards) could be charged to a non-conformer. In Slidell, it was said that "nearly every household...is either afflicted or assisting the afflicted, and all are worn out and in need of rest." In Covington, the town's seven doctors exhausted themselves going from house to house to treat the ill. Barber shops were added to the list of locations shut down. A cluster was identified at the former Ostendorf Hotel, then a tenement house, with thirteen cases and one death. In another blow to normalcy, the St. Tammany Parish State Fair was pushed back to the end of November.

In late October 1918, cases had declined enough for the Farmer to confidently report "Flu Now On Decline" above the masthead. Slidell was at that point seeing only 5 to 7 new cases a day, rather than 40 to 50 new cases at the epidemic's peak. In the Madisonville shipyards, workers stopped wearing masks. By November 9, the number of total cases in the parish had dropped to 139. There was to be further good news: the armistice was signed November 11, 1918, ending the first World War. Impromptu parades broke out across the parish in celebration: "...there was pandemonium for a time, but it was a pandemonium of joy." It appeared that the virus, like the war, was licked and under control.

Add a comment to: The 1918 Influenza Pandemic in St. Tammany Parish: Part 1