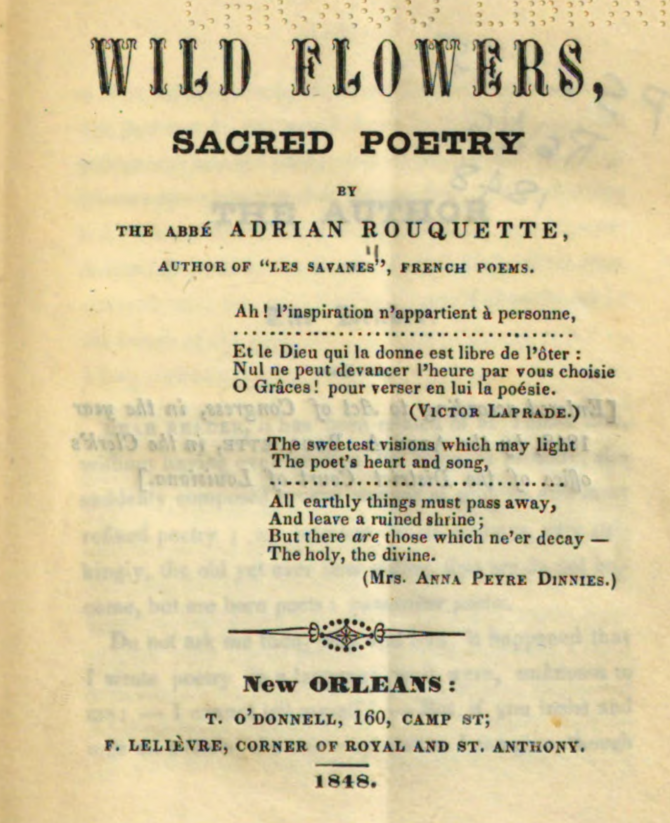

This post, second in a series on Father Adrien Rouquette, will focus on his book of English-language poems, Wild Flowers, Sacred Poetry, which was inspired by his time spent on Bayou Lacombe.

This post, second in a series on Father Adrien Rouquette, will focus on his book of English-language poems, Wild Flowers, Sacred Poetry, which was inspired by his time spent on Bayou Lacombe.

In Paris in the 1830s and 1840s, Adrien Rouquette was developing a successful writing career, with accolades from Chateaubriand, Lamartine, Emil Deschamps, and Barthelemy. Thomas Moore was particularly effusive with his praise, and wrote to Rouquette that his poems in Les Savannes "breathed forth the poetry of the purest forest flowers."

In 1848, after his return to New Orleans from Paris, and after the assumption of his priesthood, he published Wild Flowers, Sacred Poetry. The title may have been inspired by the compliment by Moore, or, more likely, by local flowers encountered on his walks through the woods of Bayou Lacombe. It is this landscape that provided the deepest inspiration for the work, and gives us unparalleled insight into Rouquette's connection with St. Tammany. There are sixteen poems in total, written between November 1847 and September 1848. Twelve of the poems were written in Bayou Lacombe; three written in New Orleans, and one written in Mandeville.

Wild Flowers was his first English-language work, and he acknowledges in an introduction addressed to the reader that he doesn't quite know why he chose to write poetry in what was "a language unknown to me." His only explanation is that he felt filled with spirit in the month of May, and put pen to paper. May was significant for being a month in which he retired to Bayou Lacombe, "the land of my mother and my boyhood's land," to find peace and quiet. This was where he could "roam and muse," among the "lonely, ever-green and harmonious groves of aged oaks, dark cedars and lofty pines". And it was in those woods, with a darkening sky overhead, and the songs of whippoorwills reverberating, that he felt visited by a "mysterious working of poetical rapture", a "mild and swaying Messenger".

He writes verse in response or in tribute to that spirit, both to help dislodge sorrow, and because he has no other choice but to write. These offerings, which he refers to as "desert blossoms," are the poems included in Wild Flowers and are his gift to the sympathetic reader. He describes them as "the spontaneous productions of an exotic and uncultivated garden -- scentless, formless, soon to fade..." And so he asks the reader, if one of the poems resonates, to "wrap it in the softest folds of an embalming memory", for which he pre-emptively extends an overflowing gratitude.

He writes about the language of friendship, about solitude, about inspiration, and devotion to his muse. He writes about his desire to better know God, the "love sublime," heavenly grace, perseverance, maidenhood, the healing power of nature, and poetry as a sacred form. He closes the short volume with a poem on his love of and faith in America - notable coming from a Creole young man who had spent much of his adult life in France. The poems are dotted with details of the bayou, and his deep affection for the landscape shines through.

For him, Bayou Lacombe and Bonfouca are the closest places he can find to heaven on earth, a place where he feels he can commune with angels and be closer to God. In fact it is an "angel-haunted wood." His poem "The Nook", written in response to a Laprade quotation, identifies Bayou Lacombe as his refuge from the cares of the world, a "verdant sea of bliss", a "sacred, deep retreat":

The Nook! O home of birds and flow'rs,

Where I may sing and pray ;

Where I may dream, in shady bow'rs,

So happy night and day.

It closes with lines identifying the bayou as a paradise, "O woody, lovely spot," where solitude is a balm and where he hopes to end his days "forgotten and forgot."

Another poem, "To My Friend...The Wild Lily and the Passion-flower," engages with the local landscape in a more detailed way. The passion flower is a hardy flowering vine, native to Louisiana, that grows in old fields of the parish; it is named in reference to the Passion of the Christ. It is also referred to as maypop. As Rouquette may have observed, it was cultivated by Indians for its fruit. The white lily of the poem may be a spider lily, with its tall stalk and long white tendrils, easy to find in any wet spot of land. Both flowers would have been in bloom in May, the period of his greatest inspiration. He pays tribute to the regality of both blooms, finding lofty purity in the lily (a queen), and powerful melancholy in the passion flower (a king). He uses the duality of the flowers as a model for life: alternating joys and sorrows, with sorrows predominating; and then makes an argument for heaven as a relief from worldly cares.

The reception of Wild Flowers was extremely positive. Brownson's Review found it "marked by much sweetness" and "full of tender and devout feeling." The Bulletin declared it to "furnis[h] in every line evidences of a pure heart, simple tastes and cultivated intellect." The Bee praised Rouquette for his mastery of the English language, down to its idioms, and noted his "purity of thought and expression" coupled with a "tender, dreamy melancholy." The Catholic Herald found only one fault with the poems--that "these Wild Flowers are not more numerous." The Daily Picayune found the poems to have a "fervent, poetic and pious spirit." And the Boston Pilot was the most enthusiastic of all the papers in its compliments to Rouquette. Among other strong accolades, they gave him perhaps the highest of all praise. They called him a "true poet."

In Wild Flowers, Adrien Rouquette crystallized the thoughts and feelings that came to him as he wandered through Bayou Lacombe, and he did so in clear speech in a language not his own. In this way, he created a deep, lasting tribute to the land that he loved so much, one that reverberates to this day.

Read Adrien Rouquette's Wild Flowers, Sacred Poetry in its entirety here, opens a new window.

Add a comment to: Spotlight on History: Father Adrien Rouquette, Part Two