It is near the end of January, the first month of a new year. By now we should all have our new calendars hanging up, which will soon be marked up and down and scribbled with all our plans. The calendar we use is something ubiquitous in our day-to-day activities. By this we plot out the year, dividing it into months and weeks, dictating when we will be at work, at school, at home, on holiday, and when we will be observing special occasions. How did we get the standard calendar we use today?

Calendars developed early in the history of human culture, as ancient people began to keep track of the changing of the seasons, and observed how the movements of heavenly bodies marked the passage of time. Some calendars are based on the phases of the moon and others on the apparent movement of the sun. For instance, the Jewish Calendar and the Chinese Calendar are lunar calendars, but the Gregorian Calendar is a solar calendar. The history behind this calendar is long and complex, but one that ought not be taken for granted, given its ubiquity in our daily lives.

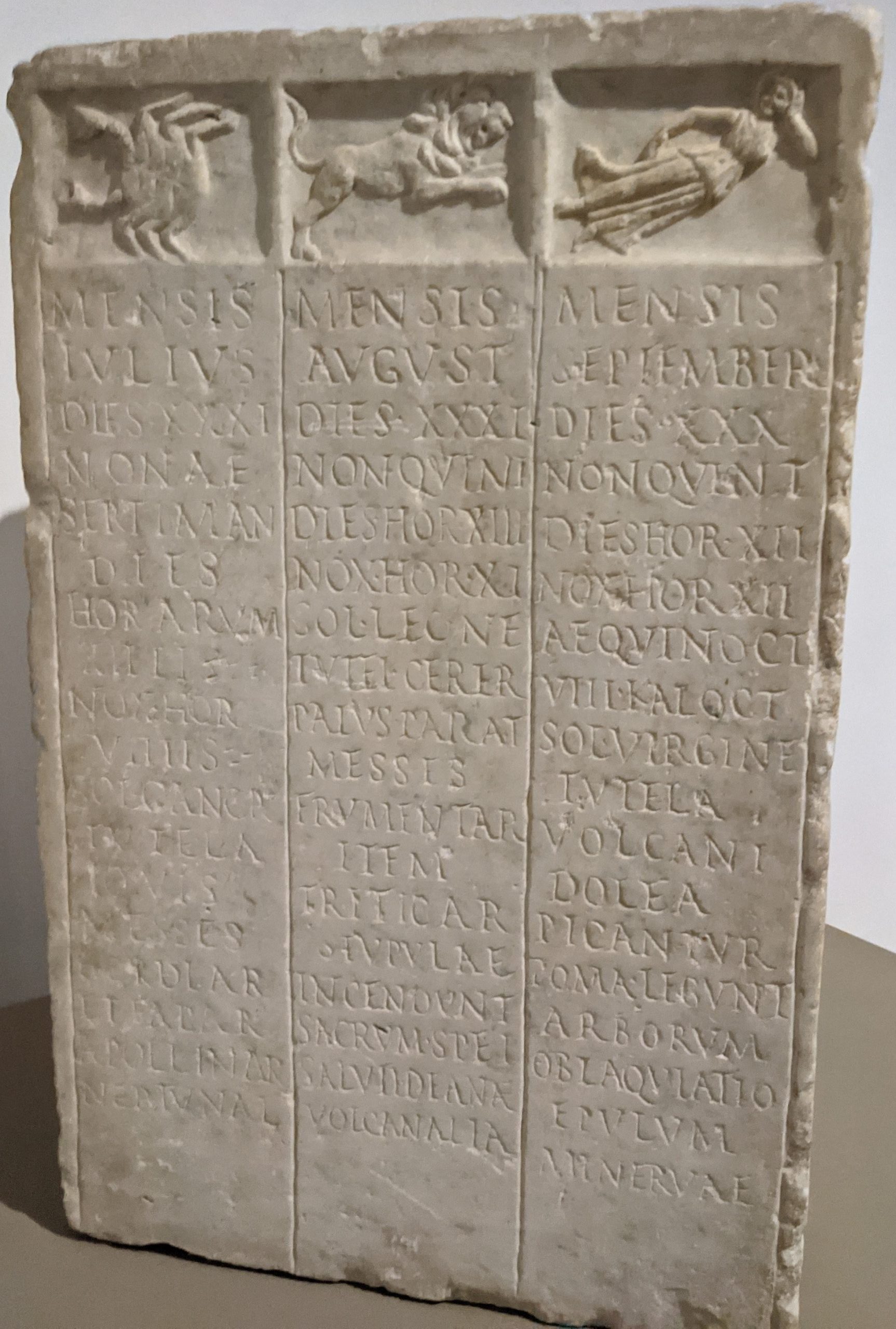

The United States, like most countries, officially uses the Gregorian Calendar. The Gregorian Calendar was established in 1582, itself being a slightly modified version of the Julian Calendar, which dates back to the time of its namesake, Julius Caesar, opens a new window. According to surviving sources, the early Romans, opens a new window had a ten-month calendar which began in March, the beginning of planting season, and ended in December after the harvest. The winter months of January and February were at first not accounted for and were only added later, which is why the months September through December have names that do not align with their placement in the year (ex. September = Seventh Month, October = Eight Month etc., see table below). Originally, theirs was a lunar calendar, and the Roman high priest would proclaim the first day of a new month, or the Kalends (from Latin ‘calare’, or call), on the New Moon. By the time of Julius Caesar, the Roman Calendar had fallen out of line with the actual seasons, and desperately needed a revision.

| English name | Latin name | meaning |

| January | Ianuarius | Janus (god of doorways) |

| February | Februarius | Time of Purification/Offering |

| March | Martius | Mars (god of war) |

| April | Aprilis | Apru (Aphrodite, goddess of love) |

| May | Maius | Maia (mother of Hermes) |

| June | Iunius | Juno (queen of the gods) |

| July | Iulius | Julius (Caesar) |

| August | Augustus | Augustus (Caesar) |

| September | September | Seventh Month |

| October | October | Eight Month |

| November | November | Ninth Month |

| December | December | Tenth Month |

Julius Caesar, having crossed the Rubicon and gained victory against his rivals, set his sights on reforming the calendar. He consulted an Egyptian astronomer by the name of Sosigenes, opens a new window, who urged him to abandon the traditional lunar calendar, opting for a solar calendar with 365 days, with a leap day added in February once every four years. In order to correct the calendar, so badly it had fallen out of line with the seasons, Caesar had to add 90 days, one time, to a single year, and thus Anno ab urbe condita, opens a new window DCCVII (46 BC) became known as the “year of confusion” and “the longest year in history”.

The Julian Calendar remained the standard in the Roman Empire and its successor states through the Middle Ages. However, once again the calendar began to fall out of line with the seasons. The Julian Calendar measured the year as 365.25 days, but the actual length of the solar year is 365.24219 days, meaning that the calendar was drifting away from the true year one day every 128 years. Medieval scholars such as Roger Bacon, opens a new window proposed reform as early as the thirteenth century, but it was not until the sixteenth century that the calendar was corrected at the behest of Pope Gregory XIII, opens a new window. Using the latest astronomical data, the pope’s astronomers decided to skip leap days in years divisible by one hundred but not in those years divisible by four hundred. This made the calendar year 365.2525 days long, much closer to the actual solar year. To realign March 21st and September 21st with the Spring and Autumn equinoxes, the days October 5th through 14th were skipped in 1582, which was far less traumatic than Julius Caesar’s readjustment. However, given the sectarian rivalries in Europe at the time, only Catholic countries adopted the new calendar right away, and Protestant nations kept to the old calendar until the 18th century. England and her American colonies did not adopt the Gregorian Calendar until 1752.

If you’re curious and want to learn more about the history of the Gregorian and other calendars, check out the following books available at St. Tammany Parish Library:

Add a comment to: Calendar Origins