As far as holidays are concerned — or perhaps as anything is concerned — New Orleans is best known for its uproarious Carnival celebration, culminating in Mardi Gras, the traditional day of indulgence before Lent, the season of fasting. But how did New Orleans traditionally celebrate the season that immediately precedes the Carnival — that most wonderful time of the year — the Christmas season?

We can’t say too much about New Orleans’ first Christmas. According to the authors of Christmas in New Orleans, opens a new window, the population in 1718 were mostly soldiers and builders who would have attended Christmas Mass in a rudimentary church of cypress logs that was decorated with a small crèche, or nativity scene, and that they almost certainly celebrated the holiday with much eating and drinking. New Orleans was little more than a few public buildings then, but the city grew quickly during the subsequent decades, and settlers from France, Germany, and elsewhere brought with them various traditions for the season. For instance, French Creoles were known for their réveillon, a feast partaken of in the early morning hours on December 25th, just after midnight Mass. German immigrants brought the tradition of Christmas trees, which became a common sight in New Orleans in the 1800s. Of course, gift giving and visiting family were just as important then as they are now, and the popular image of Saint Nicholas or Papa Noël was then ascendant.

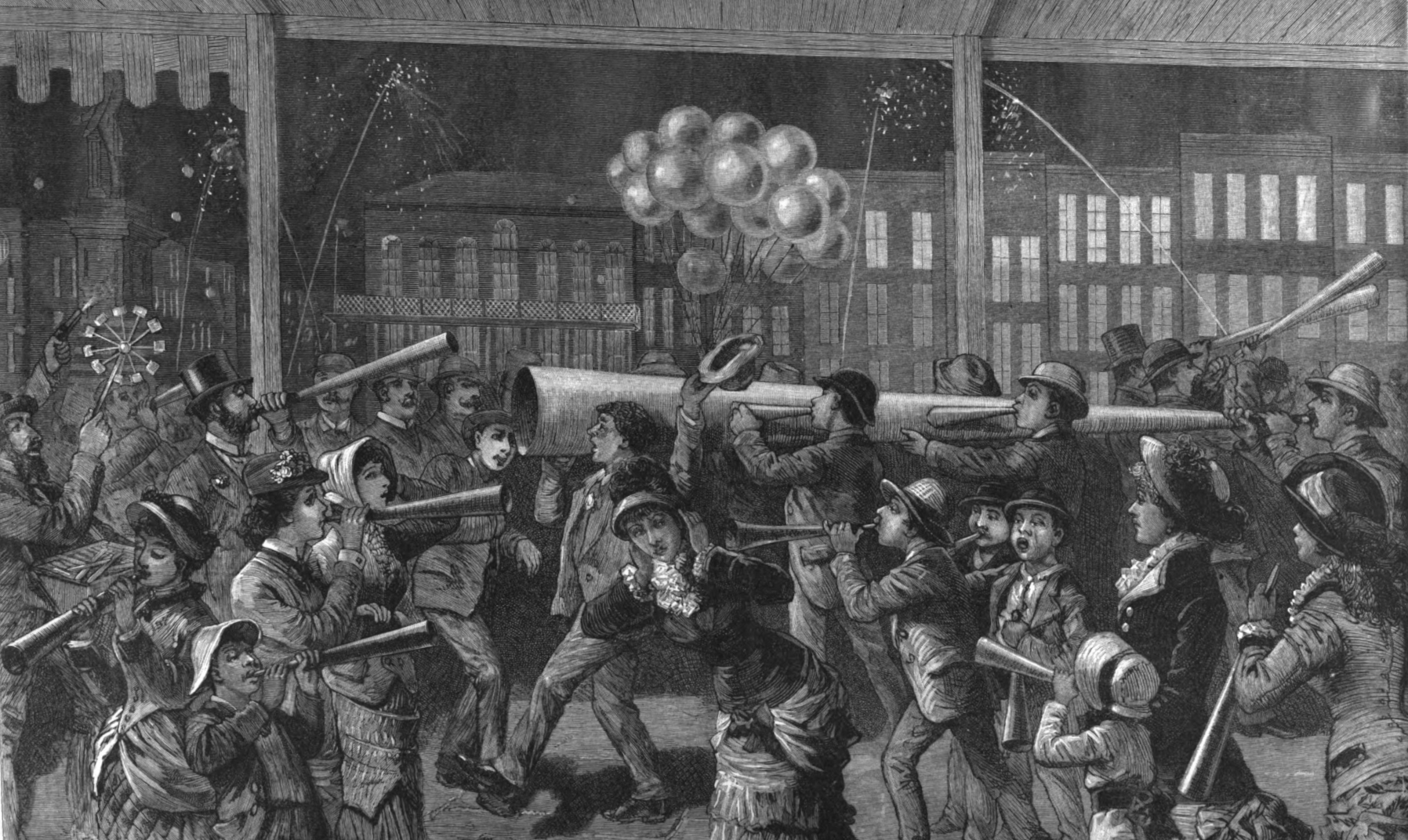

During the nineteenth century, the celebration of Christmas in New Orleans was marked for its boisterousness. Making noise was a part of the holiday cheer. Fireworks were lit and locals played music on the streets to mark the occasion. One particularly raucous ritual that arose was blowing horns, a revelry that started with children but soon was taken up by all ages. Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper related the following in 1885:

OUR artist correspondent thus describes the scene which is illustrated on page 325 [see above image]: “Heat, noise, color, essential and inseparable ingredients of Crescent City holiday-making, were predominant. A little rain had fallen during the day, and the atmosphere, damp, oppressive, and surcharged toward evening with sulphurous exhalations, gave to all objects that distant, unreal effect which is imperfectly imitated by the introduction of gauze screens in scenic representations on the stage. The distinguishing feature of this Christmas Eve was the undue and inexplicably prominence of tin horns, which, unprecedented in number and dimensions, filled the air with their barbarous discord. Two years ago they were relegated to children: to-day gray-bearded merchants, the elders among the people, are first to render night hideous. The Cotton and Produce Exchanges, after this fashion, set the evil example (turning out en masse to serenade their respective newly-elected officers): it proved contagious, and within a few hours infected nine-tenths of the community. Toy-dealers ransacked their stores vainly to supply the demand ; portentous relics of disbanded charicari organizations were dragged again to light, and tinsmiths were busily engaged, during the short time which remained, in fabricating instruments to order. Some of these were fit for a giant’s use, one being borne upon the shoulders of four men, whilst a fifth supplied the wind-power; but, fortunately, the execution was inferior to the intention, and they were not measurably more blatant than their smaller rivals. Added to the fantastic costumes and exaggerated fireworks indulged in, the netural ground on Canal Street, at the intersection of St. Charles and Royal Streets, presented a singularly picturesque spectacle. Everything was on a gigantic scale ; the human concourse, the illuminated buildings, the pyro-technical sparks and crackling, intermingle now and then with the sharper report of firearms, which, in contravention of the State and municipal ordinances, were continually drawn from their places of concealment and discharged by their reckless possessors ; but, withal, the casualties were small and the good humor great, while the tall statue of Henry Clay looked tranquilly down upon the seething, boisterous crowd below, until as the red rays of the rising sun streaked the horizon the last reveler wandered homeward.

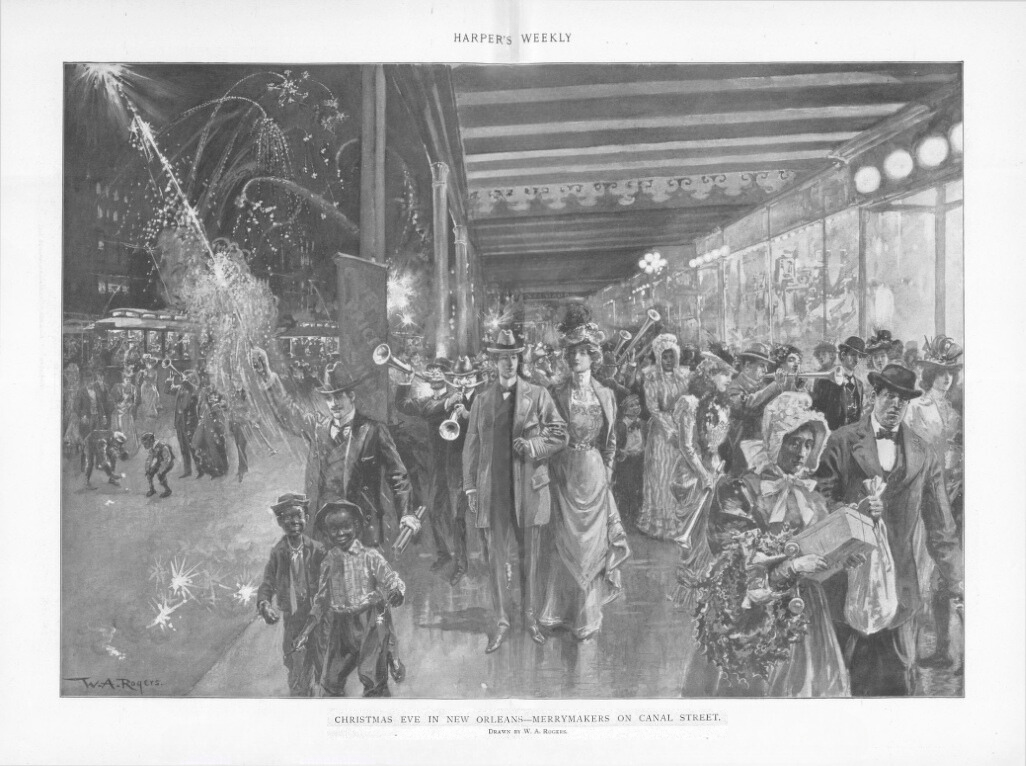

This practice was apparently still popular at the turn of the 20th century, as this illustration from Harper’s Weekly shows:

For more on the history of yuletide cheer in the Big Easy, check out Christmas in New Orleans, opens a new window. Also, check out our databases for historic newspapers, opens a new window to explore more on life in Old Louisiana.

Add a comment to: An Old New Orleans Christmas